Day 5 — HowToVer?!

15 August 2020 · recurse-centerAfter reading software versioning posts by Brett Cannon, Donald Stufft, and Bernát Gábor; I thought that I should try to summarize what I learned (for future me!).

Why do we need software versioning? We need it to snapshot each point in the software evolution process, and to follow a convention using which different pieces of software can interoperate by specifying precise dependencies.

I came across Semantic Versioning (SemVer) in 2016 when I was looking to put out some code. It fit my mental model of software versions as point-separated numbers that I'd seen in the wild. So I didn't think twice, and have used it ever since.

SemVer states that; given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

- MAJOR (breaking) version when you make incompatible API changes,

- MINOR (enhancement) version when you add functionality in a backwards compatible manner, and

- PATCH (micro/bugfix) version when you make backwards compatible bug fixes.

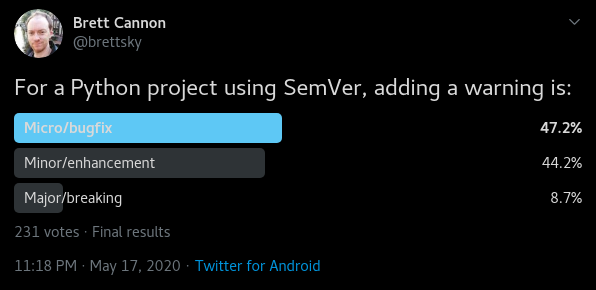

In May, Brett Cannon tweeted a poll asking people what version they'd bump if they had to add a warning, and the results were pretty inconsistent! What about dropping Python 2 support? That should be a major version bump because you're making your API incompatible for Python 2 users, right?

Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

To me that speaks volumes to why SemVer does not inherently work: someone's bugfix may be someone else's breaking change. Exceptions are especially a tricky case. They don't outwardly change an API, but they certainly can break code if a user was being careful about what exceptions they were catching (this is why Java makes exceptions part of the declared API). —Why I don't like SemVer anymore

SemVer also states that; if your software is being used in production, has a stable API on which users have come to depend and has you worrying a lot about backwards compatibility, then it should probably already be 1.0.0.

But a lot of projects don't follow this, which is why we have ZeroVer. I've also been in the same boat, because I thought that a project's API can remain unstable till it becomes "perfect" for the 1.0.0 release. But after an API has been out there for a while, can it really break compat on minor releases without causing a lot of users a lot of pain? Coming back to Hyrum's Law:

There's no guarantee that a major version will actually break you, it just might break you. But as I just mentioned, micro releases can do that, too. So then why do we try to contort ourselves into fitting into SemVer and trying to rely on it when defining our acceptable dependency versions when the numbers don't really have a consistent meaning between projects, making the concept somewhat of a moot point? — Why I don't like SemVer anymore

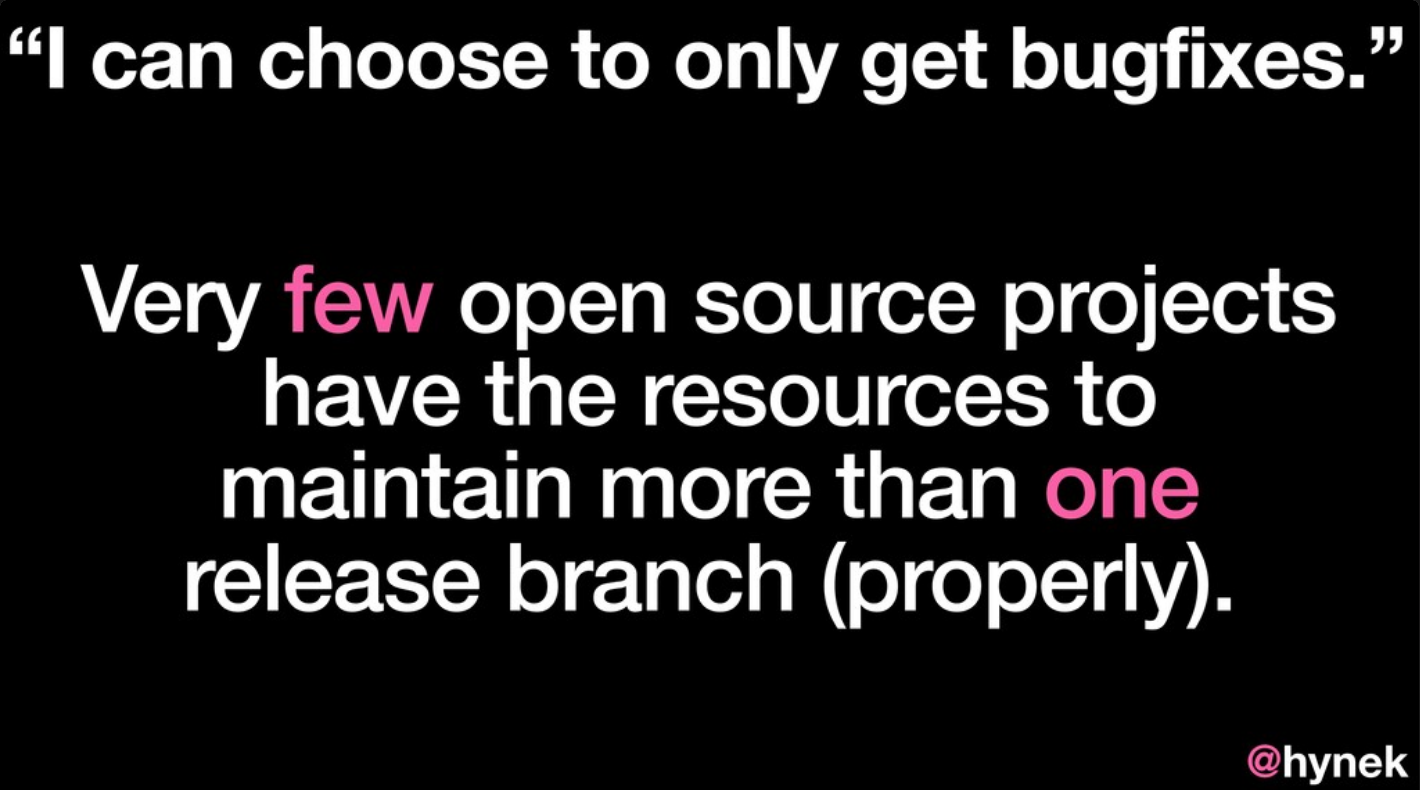

SemVer does make sense for large projects like Python, which have multiple release lines. But most open-source projects don't do multiple releases, and don't support old versions. Every new feature, bugfix and security update goes into the latest release.

Source: On the Meaning of Version Numbers

Source: On the Meaning of Version Numbers

Brett suggests that if you're stuck on ZeroVer, then why not just drop a digit and have your version be X.Y, since PEP 440 supports it. virtualenv did this when it moved from 1.11.6 to 12.0, but since then it has moved to CalVer. pip also moved to CalVer in 2018. In On the Meaning of Version Numbers, Hynek argues to not do SemVer if you're afraid to increment the major version, and give CalVer a try.

I'm starting to lean towards CalVer because it doesn't leave room for anyone's interpretation of which version number should be bumped. Every release is tagged with the date on which the release was made. Though you can't infer if a release contains breaking changes just by looking at the version number (that seems hard to do with SemVer too, as mentioned above), but that can be fixed with a well-documented changelog.

Today I also learned about GoldVer. And that TeX and Metafont use mathematical constants π and e as version numbers, adding a digit after the decimal every time a release is made. This is a reflection of the projects being very stable, with the last release 6 years ago.

Donald Knuth has stated that the "absolutely final change (to be made after his death)" will be to change the version number to π, at which point all remaining bugs will become permanent features. — The future of TeX and Metafont